the shrouded effigy enigma

- TBMM

- Aug 23, 2025

- 18 min read

Updated: Sep 4, 2025

In the ancient English church of St. Mary and St. Barlock, a mysterious slab whispers secrets from the past to whoever stops to listen. It's so shocking and unusual —an alabaster slab with a roughly incised effigy of a shrouded woman's corpse—, that when I came across the photo below I was intrigued. [image credits: Zara Handley] I've visited many churches and seen numerous ancient tombs in them, but nothing like it. It seems a representation too crude and graphic to honour someone's memory. I also wondered why the slab seemed to bear no name.

I did an Internet search and discovered a surprising story that raised more questions than answers. If the story was true, why was the slab there at all? Why was it placed where it was within the church? Why a shroud and not a proper effigy, finely dressed, like those of other tombs in the church?

Located in Norbury, Derbyshire, the church dates back to the 12th century, built and later expanded under the patronage of the Fitzherbert family, prominent landowners of Norman origin. It stands next to their ancestral home, Norbury Hall (also known as The Old Manor) and the adjoining Norbury Manor, built in the 17th century (not shown in the photo). [image credits: Britain Express]

There are a number of tombs and memorials to several members of the Fitzherbert family in the church. The oldest is that of Sir Henry, 6th lord of Norbury, knight banneret, Sheriff of Derbyshire and Nottinghamshire (1263-1264) and MP of Derbyshire in 1294 and 1307. He's represented with crossed legs, a feature often associated with crusaders, though in this case it simply indicates his profession of the Christian faith. [image credits for the effigy of Sir Henry: jmc4 - Church Explorer]

In the chancel, before the altar, two elaborate alabaster tombs face each other. The first belongs to Sir Nicholas, 11th Lord (d. 1473), High Sheriff of Derbyshire. The second, a double tomb, commemorates Sir Ralph, 12th Lord (d. 1483), son of Sir Nicholas, and his wife, Elizabeth. [image credits: thornber.net]

Sir Ralph's eldest son, Sir John (d. 1531), 13th Lord, is buried in a less prominent location: in the south chapel, to the west of the tower, against the east wall. It's a plain altar tomb, with no effigy or distinctive features. It was his brother, Sir Anthony (d. 1538), who inherited the manor upon his death, becoming the 14th Lord. A notable judge, scholar and author of law treatises, he's buried with his second wife, Matilda, as indicated by the brass-inlaid gravestone on the chancel floor, between the alabaster tombs of his parents and grandfather. [image credits: Sir John's tomb → Rita @ Find A Grave. Brass figures of Sir Anthony and his wife → jmc4 - Church Explorer]

Where, then, is the mystery slab located? And who is the woman buried under it? The slab lies between the tomb of Sir Nicholas and the wall, as shown in the following photo, taken from above. The woman has been identified as Benedicta Bradbourne (d. 1531), wife of Sir John Fitzherbert, based on one of the four shields incised at the corners, which bears her family's coat of arms. Apparently above the figure there's an inscription with the date 1531, corresponding to her death. [image credits: uncertain - Nuno Rodrigues @ Pinterest?]

Parish records indicate that Sir John and Benedicta had a son, Nicholas, their heir, and three daughters: Elizabeth, Anne, and Edith [see 1 in "Sources", at the end]. However, apparently, theirs was a rocky marriage. At first, out of curiosity, I read the Wikipedia article, which states that Sir John disinherited Benedicta from her dower rights because she had been unfaithful to him, and "denied paternity of her children", quoting this passage from his will: "Furthermore, I declare that Bennett, my wife, has been of lewd and vile disposition, and was not content with me, so she abandoned my household and company, and lived in other places, as it pleased her, and continues to do so, to my great shame and hers. For this reason, in my conscience, she has lost her right to her dower and jointure, and my movable goods [...]." [The dower was a common law that granted a widow the right to one-third of her deceased husband's lands, and the jointure a legal provision, settled as part of the marriage contract in the form of property or a yearly income, to ensure her financial support after her husband’s death. It was often arranged as an alternative or supplement to the dower.]

If we were to take Sir John's claims as true, that indeed makes Benedicta sound like a terrible person, but, in any case, I found it difficult to believe that none of the four children were his. It also seemed strange to me that, in spite of her scandalous behaviour, Benedicta had been buried in the family church, and in the chancel, no less, right in front of the altar, next to her husband's grandfather and parents.

However, when I dug some more, I discovered some inaccuracies in Wikipedia and other sources. Sir John's will can be consulted online [see 2 in "Sources", at the end] and, when I checked it out, I came across several interesting passages. Earlier in 1517, the year in which he wrote his will, his only son and heir, Nicholas, had died, and died without issue [see 3 in "Sources", at the end]. Sir John didn't pass away until 1531, so it looks very much like, after his son's unexpected death, he moved fast to ensure that the manor and the rest of his possessions did not fall into undesired hands. In fact, that much becomes clear from this heated passage, by which he excluded Anne from the will, asserting that she was not his daughter: "I declare, for various reasons and considerations—especially because I know for certain that Anne Welles, wife of John Welles of Hoar Cross, is not my daughter, and I swear this on my soul, to be judged at the dreadful Day of Judgement—that I do not want illegitimately born heirs or those not of my blood to inherit my manors or any part of them. I desire that, since the Manor of Norbury has been in my family’s name for about 400 years or more, it should continue to remain so, if it pleases God."

So actually Sir John only denied paternity of one of Benedicta's children. And ironically enough, for having criticized his wife so harshly, he wasn't exactly a paragon of virtue himself, because he had fathered an illegitimate daughter! Later in his will he refers to her as "my bastard daughter" and details the provisions he had made for her, including an arranged marriage and the bequest of household items: "I had previously agreed and negotiated with John Basseford of Bradley Ash that his son and heir, Anthony Basseford, would marry my bastard daughter, Jane Fitzherbert [...]. I direct my trustees to collect the specified yearly rent, or else forty pounds along with the arrears, for the use and marriage of my bastard daughter, Jane Fitzherbert. I entrust this matter to my brother [...] and I ask him to be kind to the poor girl. [...] Also, I wish that my bastard daughter, Jane Fitzherbert, receive all the household items I have at the parsonage."

In early modern England men faced far less social scrutiny for extramarital affairs than women. It was not uncommon for men, particularly those of higher social standing, to have illegitimate children. Such behaviour was often tacitly accepted or overlooked, especially if the man acknowledged and provided for the child. Society tended to view male infidelity as a private matter, and men were rarely publicly shamed or legally penalised for it. John Fitzherbert’s acknowledgement of his illegitimate daughter, and his efforts to provide for her would have been viewed as honourable and responsible. Likewise, his public criticism of his wife’s “lewd and vile disposition” and his denial of Anne's paternity would have been seen as a legitimate defence of his honour and estate.

At least it is to his credit that he respected the wishes of his father, Sir Ralph, who had left instructions for some lands to be bequeathed to Benedicta. Was Sir Ralph fond of her? Did he think it was only fair, since she was the wife of his eldest son and mother of his children? In any case, John Fitzherbert stipulated in his will that, whoever became his heir at his death, should honour that promise, though he set the condition that she mend her ways: "However, despite this [Benedicta's infidelity and behaviour], my father, whose soul God pardon, promised that she would have ten pounds in lands. Therefore, I direct that my male heir, by virtue of this will, shall pay her ten pounds annually in money or provide equivalent lands during her lifetime, provided she shows better character in her old age than she did in her youth. As for any movable goods, she has none, since she did not contribute to acquiring them, and therefore she shall not have the right to dispose of them, for I have already given them all away during my lifetime."

The last words of that passage hint at a legal trick he pulled out. Since his natural heir, Nicholas, had died, Sir John designated in his will that his estates, including the manor of Norbury, be inherited by his brother Anthony. If Sir Anthony died, the inheritance was to pass sequentially to his own heir, then to a relative from Uphall called Humphrey Fitzherbert, and finally to the male heirs of Sir John's daughter Elizabeth. (The youngest daughter, Edith, is not mentioned at all in the will. Maybe she died young too?) Also, he granted to these successive heirs the use and profits of all movable goods (furniture, etc.) of Norbury Hall as "heirlooms" to pass from one to another.

In a codicil added later to the will, he included an exhaustive list of those heirlooms, specifying that he was giving them in his lifetime to one of his will executors and then resuming the use of them on loan. And, as Rev. J. Charles Cox points out in his paper "Norbury Manor House and the Troubles of the Fitzherberts", this was "a cunning device to outwit his wife [...] probably suggested by his astute lawyer brother Sir Anthony." [see 2 in "Sources", at the end] This strategy, to prevent his wife from inheriting or controlling his valuable personal possessions after his death, likely exploited legal loopholes to bypass inheritance laws or dower rights that would have entitled her to a portion of his estate or goods, while preserving them for his designed heirs. Back to the slab: was the supposed shameful secret of Benedicta's infidelity the reason for the shrouded effigy? In itself, it is a rare and striking feature indeed, contrasting, as we've seen, with the more typical elegant depictions of the Fitzherbert family. In medieval Europe, "cadaver effigies" —showing the deceased in a state of decay, as a skeleton, or shrouded— were sometimes used to emphasize the transience of life and the inevitability of death, as a reminder of humility and the need for spiritual preparation. Benedicta’s slab might reflect this memento mori tradition, chosen to convey a message of repentance or humility. It might also simply reflect a cost-saving measure compared to the more elaborate effigies of Sir Nicholas, or Sir Ralph and his wife. However, this explanation feels less compelling given the deliberate nature of church burials and the prominence of the location. Burials at the time were highly symbolic, and such a placement would likely carry deeper meaning, especially in light of the family drama. Burial within a church, especially near the altar, was a privilege reserved for the wealthy, influential, or pious.

Why was Benedicta buried in the Fitzherbert family church, in spite of the shame she had apparently brought upon them? The unusual placement of the slab, its shrouded effigy and the facts and details that emerge from Sir John's will suggest several possible hypotheses.

As I delved deeper into the historical facts, I realized I'd been somewhat naive in assuming that the tombs had remained undisturbed for centuries. Actually, many changes and alterations had been made to the church. Sir Henry's leg-crossed effigy wasn't originally in the south east chapel, next to the church pews, but in a more dignified location: at the centre of the chancel, which he himself had built. Then, the tomb of Sir Nicholas, as well as that of Sir Ralph and his wife, with their elegant alabaster effigies, believed to have been commissioned by Sir John (their grandson and son) after his mother's death in 1491, were originally placed in the south chapel, closest to the east end, and at the east end of the north aisle respectively. When the church was "restored" during the Victorian era, in 1841, many elements were relocated, and that's how these two tombs ended up in the chancel. [see 4 in "Sources", at the end]

Possibly they were relocated because they are more ornate and impressive, and someone thought they were better suited to the chancel. That reasoning would make it unlikely that Benedicta's slab was relocated too. But if it was originally placed in the chancel, why could it have been placed there?

Despite Sir John’s accusations of infidelity, such a prominent location might suggest a form of posthumous reconciliation or familial duty. The Bradbourne shield on the slab seems to indicate Benedicta' family’s involvement. This could reflect a desire to maintain family unity, overriding the personal grievances expresses in the will. The shrouded effigy, rather than an elegant depiction, might have been a deliberate choice to emphasise humility or penance, reflecting the accusations against her. It could serve as a visual acknowledgement of her alleged sins, balancing public perception with spiritual redemption.

On the other hand, as mentioned before, accusations of infidelity were serious, and often used to control or discredit women. If Benedicta’s daughters were involved in arranging her burial, they might have sought to restore her reputation, especially if they believed their father’s claims were false. They might have arranged for her burial in such a conspicuous location as an act of defiance or vindication. Placing her slab in the chancel, near the altar, could symbolize their assertion of her dignity and rightful place. The shrouded effigy might then be interpreted as a sombre, dignified representation of death, emphasizing her mortality and spiritual equality before God, a silent rebuke to her husband's earthly judgement, rather than a reflection of shame.

In fact, there are other pieces of the puzzle that might support this interpretation. When I was searching for more information about Sir John's will, I unexpectedly came across a document about his brother's will [see 5 in "Sources", at the end] that quotes an intriguing passage from Sir Anthony Fitzherbert's entry on the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. It refers to a "riotous altercation" at Sir John's funeral in 1531, and a subsequent Star Chamber suit.

This altercation apparently arose because "Norbury and the other family estates were entailed (that is, legally designated) to Anthony under the will of his brother John, dated 1517, and Anthony moved into Norbury Hall under an inter vivos arrangement in 1526".

An entail restricted the inheritance of property to specific heirs, often to keep estates intact within a family line. So, as we learned before, Sir Anthony was favoured as the heir over other potential claimants, such as Sir John’s daughters and their sons. The inter vivos (Latin for "between the living") arrangement meant a transfer of property or rights during Sir John’s lifetime. This could be the strategic move to secure Sir Anthony’s control over the estate before Sir John’s death, as we've seen, and the altercation at the funeral suggests a heated confrontation, possibly involving Sir John’s aggrieved daughters, their supporters, or other relatives who felt wronged by the entailment.

The Star Chamber was an English court that operated from the late 15th to the mid-17th centuries. It was established to ensure justice in cases involving powerful individuals or matters beyond the scope of common law courts. The altercation at the funeral leading to a Star Chamber suit suggests the dispute went beyond local courts, likely because of the Fitzherbert family’s status or the complexity of the case. The court’s involvement could imply accusations of unlawful dealings or that the altercation at the funeral was seen as a breach of public order. The plaintiffs might have claimed that Sir John’s will was improperly executed, or that the 1526 inter vivos transfer was invalid.

When researching this topic, to my surprise I found 10 records of lawsuits revolving around this family drama on the UK National Archives website! Unfortunately none of them have yet been digitised, which means they must be consulted in person at the National Archives. And since I live in Spain, my curiosity won't be quenched. It would be hard for me to make sense of the records anyway, because they are written in the script of the time, that is not easy to decipher, and even though I studied Early Modern English in university, it would still take me some time. And instead of a post I could write a whole book about this!

Anyway... Three of the records refer to a dispute between Sir John and his wife. In spite of the broad date ranges of these records, it's possible to establish a logical order through their description, as this kind of legal disputes followed a sequence. The first record (Ref. C 1/506/26) is the bill of complaint that initiated the suit. In the bill, the complainant or plaintiff —Benedicta, in this case— outlined their grievances and the remedy they sought. Benedicta sued her husband at the Court of Chancery on the grounds of "false imprisonment of complainant over the house sink, and detention of her jointure since her escape". [There wasn't a standardised spelling at the time, so as you'll notice names and surnames vary: Benedicta is referred to as Benet, Benett, and Bennett and as the "daughter of John Brodhomme", which must be a clerical error for "Bradbourne". Sir John is described as "son of Rauf Fitzherbert", which is probably a misspelling of "Ralph".]

Her husband had confined her unlawfully ("false imprisonment"). It's unclear what is meant by "over the house sink". Perhaps he locked her in the kitchen or the scullery? It seems likely, however, that it was a form of punishment or coercion, preventing her from leaving the household.

We don't know the exact date of the lawsuit, but from the date range on the record (1518-1529) it is certain that it was initiated after 1517, when Sir John made his will, probably prompted, as we've seen, by his only son and heir's death in that year. As we know from the will, the marriage was strained. By then he had discovered Benedicta's supposed infidelity, and felt affronted that she had left him: "[...] was not content with me, so she abandoned my household and company, and lived in other places, as it pleased her, and continues to do so, to my great shame and hers".

Perhaps she had been staying with various relatives and had returned to Norbury Hall for some reason, and her husband seized the opportunity to confine her in the house. Or maybe she had been forcibly brought back. Whatever the case, the record's description confirms that Benedicta managed to escape, only to discover that her jointure was being withheld.

Although the jointure typically took effect after the husband’s death, it could include provisions for the wife to receive benefits during the marriage (e.g., maintenance in case of separation). Perhaps, after escaping, Benedicta sought maintenance linked to income from the jointure property, or aimed at protecting her future rights to it, and was met with an outright refusal from her husband.

The second record (Ref. C 4/127/77) contains the "answer" and the "replication". The answer is the formal written response submitted by the defendant (the party being sued —that is, Sir John), and it addresses each point raised in the complaint, admitting or refuting claims and offering explanations. It may also introduce new facts or defences relevant to the case. The replication is the plaintiff’s reply, addressing the defendant's points, clarifying or refuting their claims, and reinforcing the original allegations.

The third record (Ref. C 4/12/20) contains the "rejoinder", which is the defendant’s response to the plaintiff’s replication, typically the final stage in the Chancery pleading process before a hearing or decree.

Don't you wish you could learn what these records contain? So do I. The rest of the records I found in the National Archives can be grouped in at least two other lawsuits. Four of them centre on a family dispute involving Sir John, his daughter Anne, and his brother Anthony. The core issue is Sir John’s accusation that his wife was unfaithful, leading him to deny paternity of Anne, disinherit her, and designate his brother Anthony as his heir to Norbury Hall and other lands. The suit concerns the legitimacy of Anne, the inheritance of Norbury, and the alienation of lands promised as Anne’s marriage settlement.

In the first record (Ref. C 1/455/30) John Welles, Anne’s husband, sues Sir John over "distress" imposed on certain lands settled as jointure for Anne at marriage. As Sir John claimed Anne was not his biological daughter, he might have used this as a pretext to challenge the validity of the marriage settlement. By denying Anne’s paternity, he could argue that she (and by extension, her husband) had no legitimate claim to the lands he had previously promised. And by imposing distress (e.g., seizing crops, livestock, or rents from the jointure lands), he was asserting control over the property and its benefits. This was likely a strategic move to undermine Anne and her husband’s financial security and challenge their legal entitlement to the lands, aligning with his broader efforts to disinherit Anne.

The description notes that Sir John’s actions were "in contempt of a decree for stay of execution," meaning he seized those lands despite a court order halting such actions. This suggests a previous record is missing. That, or I overlooked some record in my search.

[Again, note the spelling variants: Wellys/Welles, and also "Wells" as we'll see in other records later.]

In the second record (Ref. C 1/590/56) it is Humphrey Welles, Anne's son, who continues the lawsuit over the lands promised as his mother's jointure, which Sir John had alienated, declaring Anne a bastard in open court at Derby. Humphrey’s involvement suggests that his father may be deceased or no longer actively involved, and he was now defending his mother’s rights. The public declaration of Anne’s illegitimacy indicates an escalation of the dispute.

"Subpoena" refers to a court order summoning Sir John and the other co-defendants to appear in Chancery and respond to Humphrey’s claims about Anne’s jointure and illegitimacy. The "commission" was an authorization to appoint local officials to gather evidence, such as witness depositions or documents, likely to investigate Sir John’s declaration of Anne’s bastardy or the alienation of her jointure lands.

The third record (Ref. C 1/590/57) shows that Humphrey sued two yeomen for refusing to testify about Anne’s alleged illegitimacy unless compelled by a court order. (Yeomen were small, independent landowners, below the gentry but above labourers in social status, who worked their own property.) The intention was to secure their testimony, and it can be inferred that Humphrey likely expected it to support his claim that his mother was Sir John’s legitimate daughter, countering the latter's allegations.

In the fourth and final record (Ref. C 1/634/7), Sir John demands that Humphrey pay him the costs of the suit in C 1/590/56. This strongly suggests that the court found insufficient evidence to prove Anne’s legitimacy or to challenge Sir John’s alienation of the lands, and ruled in his favour.

The remaining three records are all Star Chamber records, which is what I was searching for —the suit following to the "riotous altercation" at Sir John's funeral in 1531—, but none of them makes explicit mention of that episode.

However, they likely form part of one same ongoing lawsuit related to that dispute, as they involve the same parties (Sir Anthony Fitzherbert and Humphrey Welles) and focus on Norbury’s inheritance.

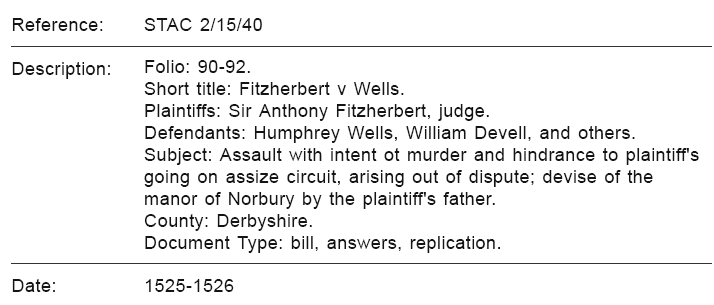

The first record (Ref. STAC 2/15/40) does refer to a violent act, where the defendant (Humphrey Welles) is accused of attacking the plaintiff, Anthony Fitzherbert, with the intention of killing him! However, the specific date (1525-1526) contrasts with the broader ranges (1509–1547) of the other two records. It looks like a separate suit addressing earlier tensions, including the bill, answers and replication.

The description shows that, as a judge, Anthony Fitzherbert served on the "assize circuit", a system where judges traveled to various regions to hear cases. Humphrey Welles is accused of interfering with his ability to carry out his judicial duties, possibly through intimidation, obstruction, or the assault itself.

The dispute also involved the inheritance or transfer (devise) of Norbury Hall through Sir John's will. The reference to "the plaintiff’s (that is, Anthony's) father" is clearly a clerical error, as the broader dispute concerns his brother John’s estate and Anne’s disinheritance.

Remember that Anthony Fitzherbert had "moved into Norbury Hall under an inter vivos arrangement [with his brother John] in 1526". Humphrey Welles challenged this move in relation with Sir John's claim that Humphrey's mother, Anne, was not his daughter, which undermined Humphrey's chances of inheriting the property.

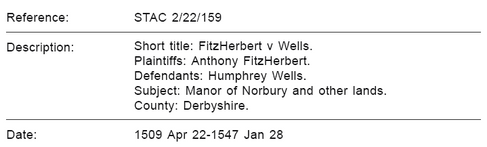

The descriptions of the second (Ref. STAC 2/25/19) and third (Ref. STAC 2/22/159) Star Chamber records provide little information beyond the fact that the dispute over Norbury Hall continued. However, we know what the outcome was, since Sir Anthony did indeed become the next lord of Norbury.

When I started looking for information on the slab out of curiosity, I didn't expect to find much, as Norbury is a small village (now part of the Norbury and Roston civil parish). Also, the Fitzherberts didn't even become members of the nobility until 1784, when Sir William Fitzherbert was granted a baronetcy. But, to my surprise, as you've seen, more information kept surfacing when I pulled at some thread. And undoubtedly even more would come out from the legal records at the National Archives. I hope someone else will take an interest in this chapter of English history and piece together the rest of the story someday. I've learned much through this journey, about this period and its customs, but most importantly, that when it comes to history, past or present —and indeed life itself—, you can't take anything for granted, as many details are uncertain, mistaken, or even distorted or manipulated. Benedicta’s slab prompts us to question how much we can trust of what we hear, read, and even see. In the end, the ultimate truth about her story is lost in the shadows of time, leaving us to wonder about the woman beneath the stone.

Sources and further reading

A Genealogical and Heraldic History of the Commoners of Great Britain and Ireland Enjoying Territorial Possessions or High Official Rank, but Uninvested with Heritable Honours, vol. I, by John Burke, 1836 - viewable and downloadable at the Wellcome Collection website.

Will of John Fitzherbert (1517), reproduced literatim almost in its entirety in the paper "Norbury Manor House and the Troubles of the Fitzherberts" by Rev. J. Charles Cox, published in vol. 7 of the Journal of the Derbyshire Archaeological and Natural History Society (1884-1885) - viewable and downloadable at the Biodiversity Heritage Library website.

A Study of a Medieval Knightly Family: the Longfords of Derbyshire, part 2, by Rosie Bevan. (Mentions date of death of Sir John's only son and heir, Nicholas.)

Notes on the Churches of Derbyshire, by Rev. J. Charles Cox, pages 271-293, 1877.

PDF document about the probate record of Sir Anthony Fitzherbert's will, dated October 12th 1537. [A probate record is a legal document related to the administration of a deceased person's estate.]

The U.K. National Archives (For the individual records of relevant lawsuits mentioned, click on the reference number links in the post.)

About the brass plates representing Sir Anthony and his wife: Hamline University digital collections

Shrouded effigies at Fenny Bentley at the blog The History Jar.

Wikipedia entry on "tomb effigy", which also elaborates on "cadaver effigies".

Comments